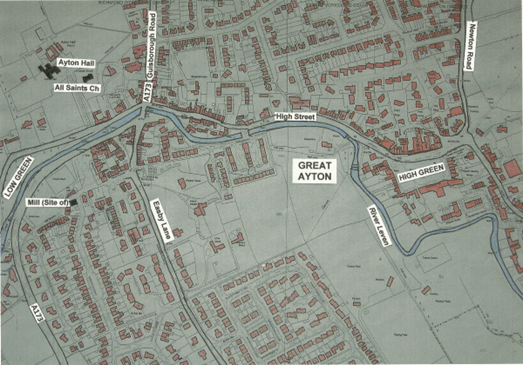

The village of Great Ayton which we see today with its extensive peripheral housing estates, has expanded from a riverside core stretching between the Low Green and the High Green.

This core area now contains retail, commercial and public buildings. It represents what most visitors remember as Ayton. There is no evidence to indicate that there was any earlier settlement where the more recent housing now stands. The Ordnance Survey six inch map of 1856 shows this linear development following the course of the River Leven with little width to the built-up area. The A173 linking Guisborough and Stokesley cuts through the village at the Stone Bridge which has for centuries been an important fording or bridge point. With two village greens, the question arises, just where did Ayton begin?

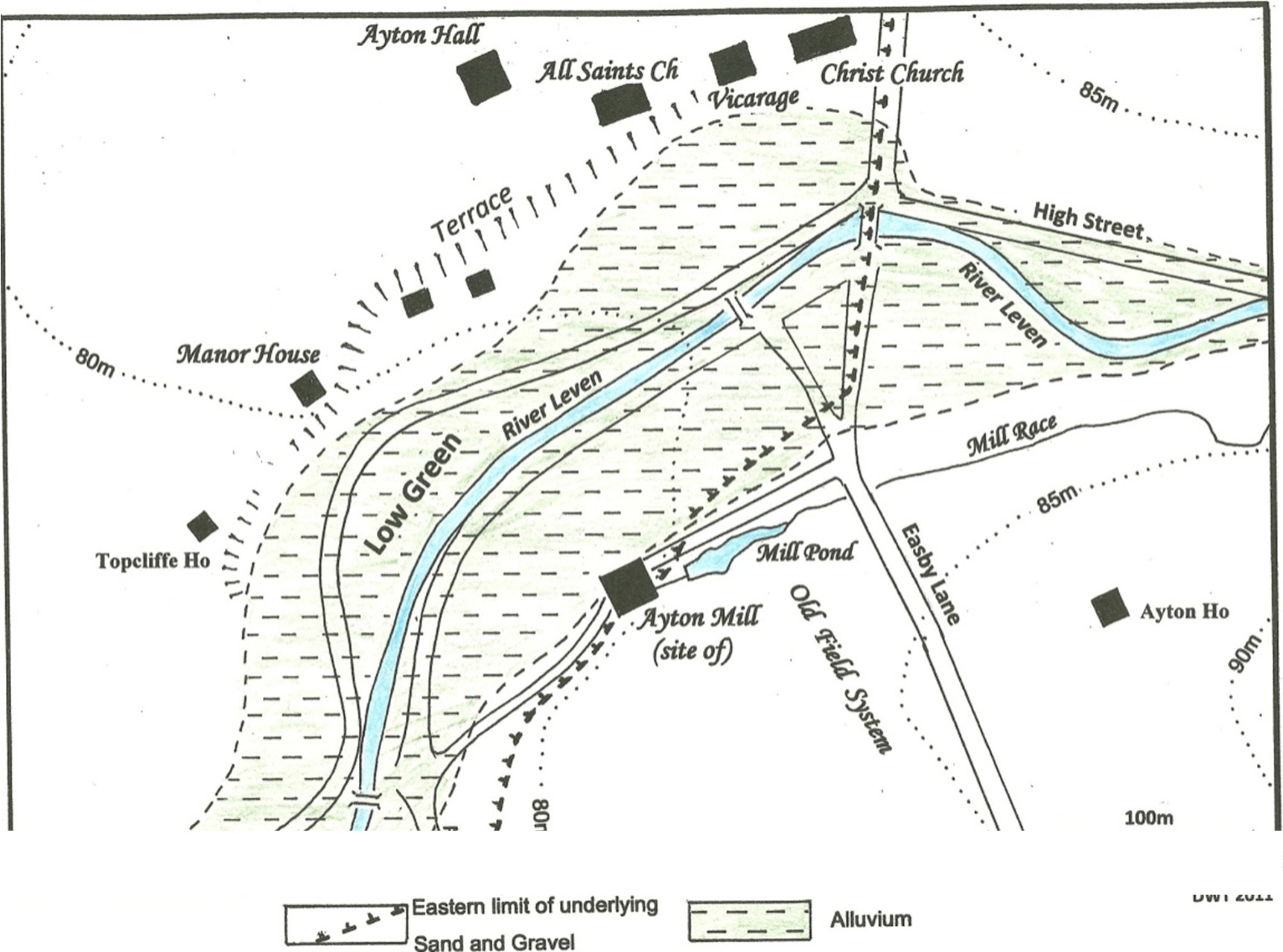

The Domesday Book, 1087, gives the first written details of the early village. Reference to a church at this time, suggests that the present Norman, All Saints Church (Figure 2) was preceded by an Anglo-Saxon wooden or stone building. lt is probable that the Normans in the twelfth century made a bold statement by constructing their new church on the same site. Anglo-Saxon sculptured stones were found in the area of All Saints in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, giving credence to this. The site is on a low terrace above the flood plain on the right bank of the River Leven (Figure 3). The same terrace provides the site for Ayton Hall and the Manor House. The present Ayton Hall was built about 1700, but is thought to have been built to replace a much earlier hall. A short distance from this terrace, but on the opposite side of the river, stood Ayton corn mill, referred to in the thirteenth century. This mill was supplied with water by a race from the dam more than half a kilometre upstream where the flood plain conveniently narrows. Grange Mill, also known to have existed in the thirteenth century, lying beyond the western end of the Low Green, was powered by water from the tail race of Ayton Mill. Old maps show evidence of narrow strip fields west of Easby Lane running parallel with the lane. This type of toft and croft arrangement is typical of very early agriculture.

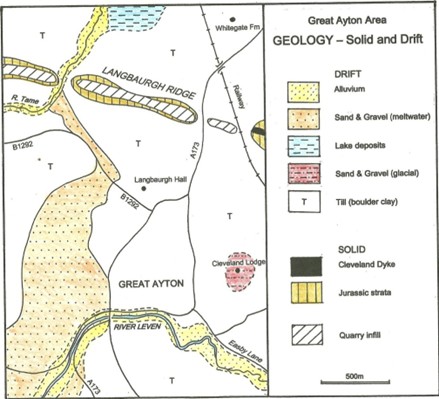

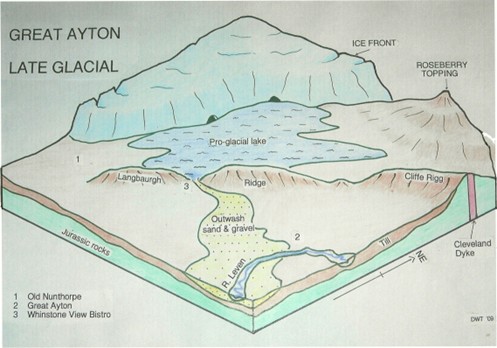

All this evidence points towards the original village nucleus being astride the Leven west of the Stone Bridge. The village green was then much larger including land on the left bank of the river. The Anglo Saxon community would have lived in timber framed houses, but as yet no direct evidence has been discovered. The flood plain of the Leven is composed of alluvium. For obvious reasons it would be early settlers. Glacial tille by (boulder clay) covers the wider area of village, (Figure 4) which would normally be very heavy for arable farming, but in this lower part of the village the problem was alleviated by the presence of a bed of well drained sand and gravel a short distance below the clay surface. Careful rigg and furrow farming would also have helped drainage of the thin clay. A geophysical survey, arranged by GACAP, in the grounds of Ayton Hall, showed evidence of isolated, but distinct areas of disturbed ground which suggest wells sunk through the clay to the aquifer beneath. This sand and gravel originated from the distinct gap in Langbaurgh Ridge where the River Tame now breaks through. lt is probable that a late glacial lake was impounded north of this ridge (Figure 5) until it over-flowed, broke through and spread the deposits in the form of an extensive fan.

The river has played a vital role in village development from pre-Norman times to the nineteenth century. At the Low Green, with such a wide flood plain it probably meandered much more than at present and could well have had a braided course. The smooth curve of the Leven which, we now see, may be a man-made landscape feature. lt is possible that this re-alignment was achieved when the weir was constructed at the west end, of the green. Three mills used power from the River Leven for grinding corn, linen manufacture, cotton production and the crushing of oil seed at various times. Dams and smaller weirs were constructed for water power or to facilitate water collection for domestic or industrial use. Tanneries needed river water, particularly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was also valuable as a waste disposal facility. Population grew and the village expanded along the river bank, especially on the north side. By 1800 a greater number of men were employed in manufacture and handicrafts than in agriculture, this in spite of the fact that agricultural production had grown following enclosures in 1658.

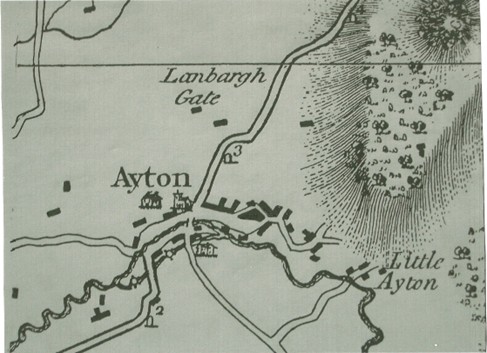

The first map showing a reasonable representation of a village plan was produced in 1771. This was printed by Thomas Jefferys (Figure 6) on a scale of one inch to the mile. By this date, the linear built-up area extended from the old nucleus upstream to a point beyond the present High Green. Even the back lane, now Skitterbeck, is shown, linking High Street with Park Square. The High Green open area seems much larger than we know it today. The north-facing side was probably built-up in the late 1700s, then replaced by Friends’ School extensions. Only the beginnings of Newton Road are shown, confirming the results of recent research which indicate that this was a nineteenth century development, linking the eastern part of the village with the A173. Aireyholme and Little Ayton are mapped without a road link to the village. Perhaps the surveyors thought these roads were of little significance.

This pattern of village layout appears to have continued with little change into the early nineteenth century. However, the growth of extractive industries, particularly whinstone and ironstone, stimulated by the arrival of the railways, brought an influx of new residents. The first phase of terraced housing was for quarrymen, followed by ironstone workers. Much of the late twentieth century expansion is associated with improved travel and the growth of Ayton as a dormitory settlement.

Fill in the form below