National Legislation and local action

The nineteenth century saw the gradual introduction of public health legislation, from a starting point of the 1842 Report into the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, by Edwin Chadwick on behalf of the Poor Law Commissioners. Three successive Public Health Acts, passed by parliament in 1848, 1872 and 1875 established a code of sanitary law. The 1848 Act met with considerable opposition: from the authorities in London who saw it as threatening their powers, from politicians concerned about over-centralisation of government, from the medical profession who resented a lay body giving advice on matters which lay within its province. Central to the 1848 Act was the establishment of a Central Board, with the power to set up local boards in places where the death rate was high or where a tenth of the poor law rate payers petitioned for one. A local board could appoint an inspector and a medical officer of health, and concern itself with sewers, slaughterhouses, burial grounds, etc. With the threat of cholera hanging over the country, the Central Board was given power to control precautions against epidemics by the Nuisances Removal Act, also passed in 1848. No sooner had these two Acts been passed than cholera broke out in Edinburgh, having arrived in a ship from Hamburg, and spread to England and Wales. Within three days of the first meeting of the Central Board there were 62 petitions for local boards. When the 1948 Acts were passed, public health was seen as primarily an issue for towns and cities, and the pioneering work was done in big cities such as Liverpool and London, which had suffered in the 1848-49 cholera epidemics (5308 deaths in Liverpool, 14,137 deaths in London).

The Local Government Board was established in 1871 to take over the responsibilities of the Poor Law Board (which had been set up in 1847) and also to be responsible for sanitation. The Stokesley Rural Sanitary Authority formally responded to the Local Government Board.

The 1872 act merged some of the local boards and consolidated existing legislation. In rural areas local health administration was devolved to Rural Sanitary Authorities which came under the aegis of the Board of Guardians of the Poor Law. The Stokesley Rural Sanitary Authority was established in 1873, and covered Yarm, Stokesley, Ayton and the other Cleveland villages. Their meetings were held in the Board Room of the Stokesley Union Workhouse at Springfield. They appointed a medical officer of health, Dr William Guthrie Forbes, and an inspector, Joseph M Mease. Although it was no doubt convenient to pass public health administration to the existing Poor Law officials, this often resulted in a narrow and legalistic interpretation of the law, and a failure to take advantage of its many provisions, such as the authority to build hospitals. However Stokesley seems to be exonerated from this accusation, through energetic medical officers of health, especially Dr Yeoman.

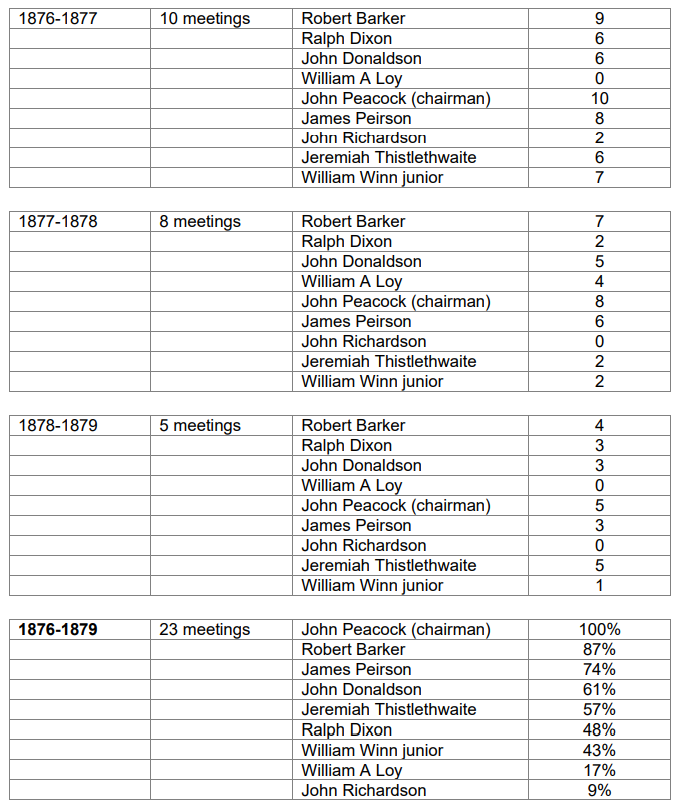

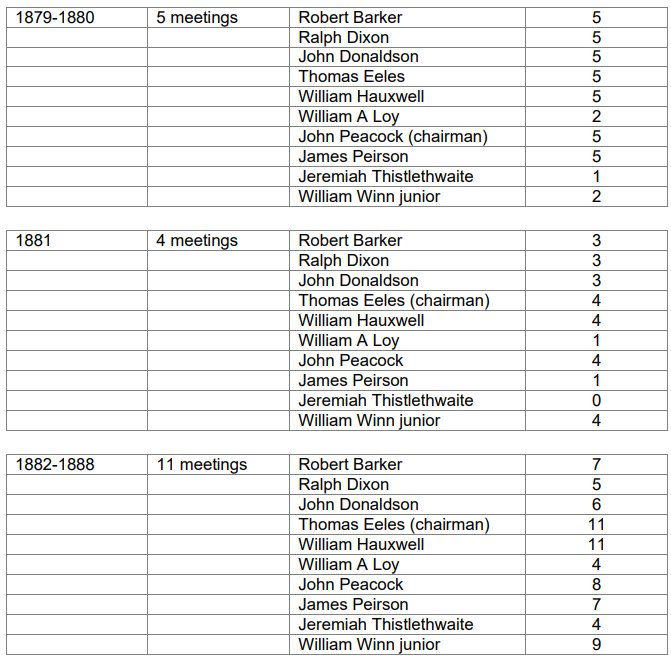

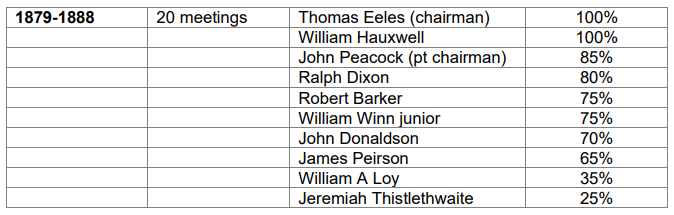

The 1875 Act generally consolidated provisions of previous legislation, and gave a comprehensive list of the powers and duties of local sanitary authorities. These included sewerage and drainage, scavenging, gas and water supplies, provision of public lavatories, control of nuisances, the right to stop the building of houses with outside privies, inspection of food, control of infected bedding, and the provision of hospitals. Local government districts were designated as sanitary districts, and the local board became the sanitary authority. Sanitary authorities could appoint parish boards, and this is how the Great Ayton Sanitary Committee came into being. The first committee of nine members was appointed by the Stokesley Board of Guardians on 3 June 1876, and held its first meeting eleven days later. It is not known what criteria the Stokesley Guardians had in mind when appointing the Ayton Parish Committee but, for the most part, they were active and conscientious, enthusiasm overcoming their lack of knowledge and experience in public health. Examples of this approach can be seen in their willingness to listen to professional engineers, their determination not to be thwarted by the likes of Henry Kitching and E H Wynne Finch, and most of all, by the construction of the 1899 Drainage Scheme.

Local boards were abolished by the Local Government Act of 1894, and urban and rural district councils introduced. This legislation marked the end of the Great Ayton Parish Sanitary Committee.

The 1875 Act stood for sixty years until the 1936 Public Health Act. This was again a mainly consolidating piece of legislation, since there were numerous other acts on specific aspects of public health, such as the 1866 Sanitary Act

which compelled local authorities to set up sanitary authorities and appoint inspectors who could force landlords to remove nuisances. The 1936 Act did include the control of smoke nuisance, but this was not effectively dealt with until the Clean Air Act of 1956.

Political conflicts

It has already been said that there was plenty of ‘establishment’ opposition to the early public health legislation. The pressure for such legislation came from radical politicians. The landed gentry and upper classes had their own private arrangements for waste collection and disposal, and lived away from the squalor of the majority of city dwellers. Even although they, as everyone else, were at the mercy of epidemics such as cholera and typhoid, the direct connection between infectious diseases and sanitation was not well understood.

This conflict appears to have echoes in the local situation in Great Ayton. Members of the local committee were predominantly what would later be called the middle classes, tenant farmers, businessmen, with a good proportion of non-conformists, especially Quakers.

Henry Kitching’s refusal to sell land for the disposal facilities (indeed, given his position in local society, he might have even been expected to donate the land).

Dr Loy’s apparent apathy towards the committee (one might have assumed that the committee’s work would have been of particular interest to the village doctor). He was absent from all nine meetings in the committee’s inaugural year of 1876, managed fewer than half the meetings in 1877, and thereafter only averaged about one meeting per year.

Edward Heneage Wynne Finch was a notable Stokesley figure, a County Councillor and a Justice of the Peace. He lived in the Manor House at Stokesley.

Henry Kitching was one of the sons of Alfred Kitching. Alfred was a wealthy Darlington businessman, who retired to the country and built Ayton Firs. Henry built The Grange

With the completion of the ‘Drainage Scheme’ in 1899, Great Ayton was the first community in the Stokesley RDC area to have a proper system of drainage and sewage treatment. The small village of Kirklevington followed in 1907, but it was not until 1932 that Stokesley itself had a sewage treatment works. There are two probable reasons for Ayton’s pioneering achievement. At a time when local populations elsewhere in the district were stable, Ayton was expanding due to the increased employment in whinstone and ironstone extraction. The rush to erect dwellings in the California area led to problems with drainage, increased pollution, and public pressure to improve matters. There seems little doubt that many members of the Ayton Sanitary Committee were conscientious and persistent in the face of opposition from local landowners, landlords and the Stokesley authorities.

Small pox

The Great Ayton Committee’s concern over small pox, from February 1898, were prompted by the outbreak of the disease in Middlesbrough on 22 November 1897. The disease spread rapidly, and by the end of February there had been 684 notified cases. The Middlesbrough authorities had learned from the previous epidemic of 1871, and responded with mass vaccination and the rapid erection of temporary buildings for isolating patients. These measures were successful, and by June the epidemic was over. However there had been 804 cases of small pox resulting in 202 deaths. The Ayton Committee was unable to set up any isolation facilities, but fortunately Stokesley RDC was the only district adjacent to Middlesbrough which did not have a single case of small pox at that time.

The Middlesbrough Borough Electrical Engineer at the time of building the Transporter Bridge (1907-1911) was H M Taylor. It is possible that this is the engineer who was engaged by the Ayton Committee.

Throughout the life of the committee there were only two clerks, Joseph Longstaff from 1876-92 and John Dixon from 1892-1989. Judging by John Dixon’s spelling, the Friends’ School education may not have been as thorough as one might imagine.

References

Public Health and Community Health Services

Yeoman’s Acres – Public Health in Stokesley Rural District 1899-1939

Dennis W Tyerman

Bilsdale Study Group, April 2007

Great Ayton Sanitary Committee Minute Book

Fill in the form below